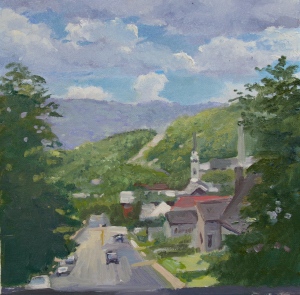

At my easel during Plein Air Easton (MD)

I have new reasons to ask myself about my objective in participating in a plein air festival. Others seem to be asking themselves the same questions, so it might be helpful to review some of the statistics, published opinions, and inner workings of events. Being a participating artist gave me an entirely new way of evaluating whether or not such events are profitable, career building, and fun. My 35 years as an art magazine editor, juror of selection, awards judge, and critic didn’t prepare me for actually competing in this kind of painting event.

I recently had the privilege of participating as an artist in several of the top plein air events in the country. I was joined by artists who committed a significant amount of time and money to compete, even considering that most were provided free housing and several banquet meals. Many of those men and women were left wondering how to measure their efforts and results.

I’ve been a dedicated plein air painter for 30 years, but until recently I have only painted with friends or participated in events in which there was little pressure for awards and sales. I painted what interested me and didn’t concern myself with achieving specific objectives except for an infrequent exhibition in which I included my outdoor paintings. The recent events have been much more competitive, especially since in previous years I was rejected by the jurors of the same competitions. I thought more about the three digital images I submitted, and I put more time and effort into the two, three, or four paintings I exhibited in the awards shows. That raised the stakes for me, as did the information I was receiving about other artists spending 15 – 20 hours on each of their competition paintings, sometimes from dusk till dawn.

There are many positive aspect to being a participant in a plein air event, both on a personal and a professional level. One has the chance to talk with other artists; learn about materials and techniques; compare one’s paintings with others created in the same location; and gauge the reaction of those other artists, collectors, and observers. There is also the possibility of winning awards, selling paintings, receiving commissions, and making progress in one’s skills and style of painting.

Before I question any aspect of these kinds of events, I should first recognize the staggering amount of money and effort that goes into making these opportunities available to me and other artists who join the events. Volunteers and staff members spend months in advance trying to increase award purses, smooth the daily procedures, prepare for an exhibition, promote participation and sales, and offer every comfort possible to the artists. Families open their home and provide accommodations, meals, snacks, and warm hospitality to the participating artists. Those volunteers and staff members offer a valuable service to artists and I wouldn’t want my comments to suggest otherwise.

I should also point out that I sold from one to four paintings in each of the recent competitions, and I won an award for Best Composition in Plein Air Easton. I don’t think my comments reflect a frustration about not being recognized by awards judges or collectors.

All that said, the harsh reality of competitive plein air events is that the applications of many top artists are routinely rejected by jurors because of the number of applicants; only about 25% to 33% of the paintings created will actually sell; three or four of the artists will generate a disproportionately high percentage of total sales and revenue; and only 5% to 20% of the artists win awards. That means it is likely that even the most talented and accomplished artist can expect rejections, poor sales, and no awards. Numbers provided by The Avalon Foundation that runs Plein Air Easton tell part of the story. The number of paintings sold between 2009 and 2014 has ranged from a low of 124 to a high of 201; the average selling price ranged from $1066 to $1519; the median selling price landed between $795 and $1200; the highest price paid was from $3500 to $7,100; the total number of participating artists is now 58 individuals; and the total number of paintings created was roughly 600. A quick review of those numbers shows that about one-third of the paintings sell during the annual event in Easton and two-thirds go home with the artists.

Plein Air Easton is arguably the most successful of all the plein air festivals with two awards of $5,000; a potential of ten days for artists to paint and sell (including the pre-festival events); and now a top-selling price of 9K or 11K (unofficial results to date). Other events have grown in size and stature, and the auction of quick draw paintings at the Door County (WI) event is an unbelievable phenomenon to witness. So too is the sales activity in Telluride (CO), Laguna Beach (CA), and Forgotten Coast (FL). However the percentage of sales and the average price paid is likely to be the same or lower as in Easton.

The cost to participating artists can be substantial when one considers that artists who are on the plein air circuit routinely fly from California to Maryland, from Vermont to Wisconsin, from Tennessee to California, and from Oregon to Colorado — often rushing from one event to the other with no time in between to stop at home. They must arrange to have their painting supplies, outdoor equipment, clothing, and 15-20 frames available at each venue, frequently relying on friends and family members to replenish their supplies.

Despite all these draw backs, hundreds of artists still pay entries fees and hope for acceptance into plein air festivals. But is it wise for them to continue indefinitely or should they consider plein air festivals a short-term means to a long-range goal? The answer may be found by examining the long careers of the best known painters. Most have stopped participating in plein air festivals because their prices are now well above the average, they keep all their sketches to use in the studio, or they no longer have fun hanging out with large groups of outdoor painters.

Connecticut artist Paul Bachem recently confessed that he was about ready to reduce the number of events in which he might participate. Here’s the comment he made when artist Lori Putnam posted a question on Facebook: “I’ve just finished my sixth year at Easton (writing this from my host’s house in fact) and while I agree about the friendships, getting to see what everyone else does and how they go about doing it, sales, awards, etc., I’ve come to feel that it is time for me to take a break. With all there is to enjoy about them, these events have at the same time always felt like grueling endurance tests to me and I know I don’t do my best under those conditions. I’m not trying to say anything bad about them…it’s just how I’ve come to feel about how they relate to/effect me.”

Colorado artist Dave Santillanes offers a more amusing reason for jumping off the plein air merry-go-round: “I’ve just been doing them in hopes of meeting my future wife. Mission accomplished. (smile emoticon) Now I’ll probably move on to other shows. But in all seriousness they are a fantastic venue for networking. All my current galleries “discovered” my work at plein air events. And I’ve met some of my best painting buddies at them.

Unlike most of the artists now on the plein air circuit, Californian Jim McVicker pursued a completely different career path even while relishing the opportunity to paint outdoors: “I have painted plein air for the past forty years but just recently, last October, participated in my first plein air event. I never realized what a great experience it would be. To meet all the great painters I now know, makes me realize how connected we all are and how many of us are out there. To share a passion with other like mined people is so rewarding. It’s also opened up connections with new collectors and the chance of sales and awards adds something different to the experience of painting with other painters. I will say, there is nothing like working plein air or in the studio on your own.”

So the point I want to make is that plein air festivals can be very competitive and stressful, and a relatively small number of participants actually win awards and sell enough paintings to make their participation profitable. The only guaranteed benefits are learning and developing friendships, and while those may be worthy rewards, they can be achieved under less stressful circumstances. The conclusion professional artists have come to is there is a point at which they will stop or greatly reduce the number of pleiin air festivals they join. Hopefully the events will position them to be better at selling through galleries or websites, enriched by the friendships they have made, better known to students and collectors, and more visible within the art community.